I

highly recommend that one listens to the “Millennium Actress Original

Soundtrack” whilst reading this piece of analytical content about it. It is one

thing to merely read about music, but it is something entirely different to

hear it for oneself. LINK. Enjoy!

After

my initial viewing of “Millennium Actress,” I was both fully in love and firmly

committed to the idea that the music itself holds tantalizingly animated and

evocative clues to the story, themes, and overall experience of the film as a

result of the impact the final song, titled “Rotation (LOTUS-2),” had on me. Despite

the linguistic disparity in it being sung in Japanese, I believe that the

feeling that the song gave me was highly indicative and reflective of that film

that I had just experienced. In short, the music made perfect sense to me as a

wonderful theme at the end of the film, wherein it takes all the ideas present

in the film and furthers them to a thematic conclusion all within a decisive,

albeit short, musical piece.

Upon listening to the

full soundtrack in far more careful bouts of enjoyment and analysis, it seems

as though the entirety of the film’s music is carefully crafted to reflect and,

more importantly, further what is committed to the screen in animated form. In

essence, the music of “Millennium Actress” is in and of itself an illusion

specifically because it reflects many of the same obvious and not so obvious

symbols, ideas, and themes that the film exhibits in its runtime, with it being

filled with elements of dreams, fantasies, and the every-present state of

reality in an objective and subjective sense.

Indeed, it seems as

though the film’s director, the late Satoshi Kon, really was right when he

called working with the soundtrack’s creator, Susumu Hirasawa, a “dream come

true” because it really does seem like it helped make “Millennium Actress” the

stellar and intricate film that it is, wherein the two connected works of art

are both describable and indescribable at the same time. In much the same

manner as Chiyoko’s willful and endless chase of the painter and the girl she

once was, Hirasawa’s music, along with a central piece of supplemental

material, is one of the key things that seems to help bind the millennium and

lifetime-spanning illusion of “Millennium Actress” into a single continuity

that can and will endure until the end of time.

The

story of how “Millennium Actress’” music came about is somewhat similar to the

story of how Genya came to give Chiyoko her long-lost key and tape an interview

with her for a documentary after being a devoted fan of her work for a good

portion of his own life. However, the real-world counterpart is not so

fantastical and coincidental so much as it seems like it was simply two artists

finally connecting with one another in order to produce a jointly-made work

that highlighted their strengths and style. In essence, Satoshi Kon and Susumu

Hirasawa were cut from the “same cloth” as far as style, themes, and influences

while making their artistic careers out of entirely different mediums, with one

being music and the other being, at least stylistically, animation.

Kon

had been a fan of Hirasawa’s work for many years prior to the former making his

directorial debut with “Perfect Blue” in 1997. At that point, Hirasawa had been

making Japanese electro and techopop for roughly two decades, wherein his work

with the band P-Model was successful before he launched a solo career in 1989. It

was not until Kon had started work on “Millennium Actress” at the turn of the

millennium that he got his chance to work with the musician. To quote Kon

himself: “When I started developing the story, I wanted to use his music so

badly…This film could not be ‘Millennium Actress’ without Hirasawa’s music.” In

that sense, it seems as though Kon actually created the film with a specific

soundtrack in mind from the very beginning, with the music being an integral

part of the film and not the afterthought that some films, both live-action and

animated, seem to believe it to be. The music of the film was very much crafted

with the same influences, themes, and style that the animation and story were

crafted from, with illusions, dreams, and reality all melding together into one

seamless continuity thanks to that music coming from a similar mind as the

person that created the overarching work in the first place. In short, the story

of making of the film’s soundtrack may be seen to have set that music up to

make the reflective and transformative properties of itself a key part of the

film in said music being crafted by similar minds, in similar styles, and for

the one singular purpose that is the film’s illusion itself.

With

the story of how the music of “Millennium Actress” came about now out of the

way, one can now delve into the vast soundscape of the music itself, with its

many bombastic, contradictory, and anachronistic pieces interspersed with

delightfully poignant pieces that wholly reflect and transform the scenes to

which they are set.

There

are a total of twelve pieces in the official “Millennium Actress Original

Soundtrack.” The first eleven tracks include:

Parts

of these loan themselves from other pieces in Hirasawa’s oeuvre, with the three

“Chiyoko’s Theme Mode”(s) being crafted in part from his song “Propeller of the

Wise Man.” The tracks “Lotus Gate” and “Circle in Circle” are also derived from

“Landscape-1” and “Kun Mae #3).

However,

there are three pieces out of these eleven tracks that are of particular note:

“Prince of Key,” “Run,” and “Actress in Time Layers.” These three tracks beautifully reflect and

transform the scenes that they are set to in their own particular ways to great

emotional and thematic effect. For example, the title and general feeling of “Run”

is an accurate representation of the theme of the scene it is set to, wherein

Chiyoko, on her endless chase of her painter, whisks herself through the years

from the era of the late Tokugawa Shogunate, all the way through the Meiji

Restoration, to the high-life, prosperous days of the 1920s all in a few simple

transitions. This particular piece is a very uplifting and somewhat loud or

bombastic piece that really gives one the feeling of Chiyoko’s continued chase.

It is no so much loud for the sake of being loud as it is loud for the sake of

highlighting the consistency with which she pursues the painter, almost in a

cyclical fashion due to the background melody that repeats a number of times

through it the track.

In another example, “Actress

in Time Layers” is almost pivotally important due to its place as the music

backdrop to Chiyoko’s frantic, albeit committed, dash to Hokkaido after finding

her lost key and receiving the decades-old letter from her painter. The

background sound of what seems to be a simple snare drum or even a triangle

(I’m no musical expert…) does an extremely effective job at reaching up the

stakes of Chiyoko’s dash, wherein it seems to be always building and

ever-present with no end in sight. Reflecting an idea of “Run,” the background

seems to have an almost haunting continuity throughout its runtime, with it

never ceasing or even slowing down, almost reflecting Chiyoko’s slow and

methodical, but still abundantly committed, chase of her “prince charming.” The

vocals in their piece are haunting in and of themselves, especially due to the

inclusion of the visuals of the wraith taunting Chiyoko. The track also seems

to itself climax a few times throughout its runtime, thereby reflecting the

“mini-climaxes” and problems that Chiyoko has to deal with on her northward

dash. In effect, “Actress in Time Layers” reflects the pivotal and climatic

scene it is set to in a very effective and transformative way, with the tension

of the scene being tuned up and the feeling of Chiyoko’s frantic dash being

firmly imparted in the ears of the audience.

In the final instance,

the track “Prince of Key” seems to be very important due to the fact that one

can retroactively hear all of the various other pieces of the film’s music

within said particular piece, wherein there are elements of “Rotation

(LOTUS-2),” “Chiyoko’s Theme Modes,” and “The Gate of Desire.” These pieces all

seem to meld together into a very fluid and serene piece that reflects the

visual of Chiyoko wandering a destroyed Tokyo after the end of World War II,

during which she finds the memento that the painter left for her during their

shared winter night all those years ago. In the scene itself, it may be said

that Chiyoko, despite being surrounded by the ruins of her country and home,

resolves to follow the painter and the girl that fell in love with him and the

dream he shared with him upon discovering the memento that he left for her on

the storeroom wall, which happens to be a picture of that young girl and the

phrase “Until we meet again.” The music seems to reflect this sentiment in its

serene and peaceful quality, along with its rotation-like background sound and

melody. Overall, this piece reflects the memento that Chiyoko finds in it being

partially a visage of a bygone age that one can never grasp again. In fact,

elements of this piece is also played during the scene where Chiyoko and the

painter share their fateful conversation in the storeroom. In effect, this

piece seems to reflect the very essence that Chiyoko is chasing: the portrait

of a young girl caught up in the dream of one day meeting her destined “prince

charming.” Furthermore, the title of the piece itself is reflective of the

status of both her key and her “prince” wherein the painter is embodied in the

key itself, which is the most important thing there is to Chiyoko as it allows

her to forever hold onto and chase the young girl that imbued the key with that

meaning. The painter is the “Prince of Key” because he has seemingly been

fatefully tied to the state of the key in Chiyoko’s eyes, with the loss or

gaining of the key hailing drastic and long-lasting changes in her life, for

better or worse. Despite the fact that her painter died during the greatest

conflict in human history, her prince, key, and chase still remain in the form

of this track and the memento that Chiyoko finds in the ruins of her home. This

reminds her, Genya, and Kyoji, and by extension the audience, of her chase and,

more importantly, what it meant to her, thereby cementing her path in life

despite a wholly transformed world and society. All in all, these pieces almost perfectly

reflect and transform the scenes that they accompany due to their own unique

qualities and how they were created in the first place.

In

contrast to the eleven other tracks, the final piece of the soundtrack may be

said to represent and reflect the whole of “Millennium Actress” in just under

four minutes of music due to it evocative and poignant lyrics and its

all-important place as both the end credits song and the piece that seems to

send Chiyoko off into eternity. With that, the track’s lyrics are:

“The golden moon causes millions of dewdrops to ascend

Your battered dreams, which come to this prison of night, bloom

Flickering, in this time; come, tens of thousands of dawns

The fleets of ships, which travel in parallel, launch on all your days

Your battered dreams, which come to this prison of night, bloom

Flickering, in this time; come, tens of thousands of dawns

The fleets of ships, which travel in parallel, launch on all your days

Like the clouds which move, and are born at random

Your voice, which knows a thousand years, echoes in the moon

Your voice, which knows a thousand years, echoes in the moon

The blooming samsara oh

The blooming lotus oh

Echo, for a thousand years oh

Echo, in every second oh

The blooming lotus oh

Echo, for a thousand years oh

Echo, in every second oh

The distant past, and the distant today will still be here even tomorrow

Golden days will exist all at once, if the forgotten you awakens

The stars which travel in parallel are now reflected like metaphors

The flowers in the field, which bloom at random, are all remembering you

Golden days will exist all at once, if the forgotten you awakens

The stars which travel in parallel are now reflected like metaphors

The flowers in the field, which bloom at random, are all remembering you

The blooming samsara oh

The blooming lotus oh

Echo, for a thousand years oh

Echo, in every second oh

The blooming lotus oh

Echo, for a thousand years oh

Echo, in every second oh

The blooming samsara oh

The blooming lotus oh

Echo, for a thousand years oh

Echo, in every second oh.”

Echo, for a thousand years oh

Echo, in every second oh.”

In reading these lyrics for the

first time, especially for a non-Japanese speaker, they seem to be both

confusing and disorientating in the many different things that it references.

Many of the references and comparisons present in this song are allusions and

metaphors for what the title of the piece denotes, rotation, along with the

essence of Chiyoko’s life. In describing the lyrics, one must piece together

understanding by systematically uncovering and chaining together the meaning of

the allusions and metaphors, thereby yielding a huge part of the track’s

significance as to why it may be considered the theme song of “Millennium

Actress.”

In

the case of the opening line, the “golden moon” may be seen to represent

eternal chases and pursuits that can take one to the heavens and back in

Japanese mythology and storytelling, and the “millions of dewdrops” may be a

metaphor for the ordinary life in their formation due to the condensation and

collection of water upon all that reaches toward the sky. The second line keys

into the idea that one’s dreams become “battered,” disillusioned, and warped

throughout the course of their life due to the weight and the “prison of night”

that is the above dewdrops. In their ascension, the lifting dewdrops of ordinary

life are said to allow for those “battered dreams” to take a new shape and fully

“bloom.” The third line’s “tens of thousands of dawns” seem to be an indication

that such a lifting of the dewdrops of ordinary life will occur throughout

one’s life if one does a specific action to allow for said process to happen.

The fourth line’s statement that “the fleets of ships…launch on all your days”

may mean that these thousands of dawns may also be represented the launch of

either aquatic ships or even the spaceships that are seen in the film, with the

latter seeming to reflect the image of a rising sun or coming dawn in its

ignition sequence and liftoff. The “parallel” description in the fourth line is

intriguing in its specificity, meaning that it has a greater significance in

its placement; however, it seems to be a reference to the fact that many things

are born from a single source and that two entirely different things may be

bound together by a small, but not insignificant, thread of fate. While the

ships are on different journeys, it seems that the fact that they have a shared

connection, in them travelling in parallel, is the thing that holds them

together, with this idea being represented by the connection between the

painter’s chase of his painting in Hokkaido and Chiyoko’s own pursuit of him

wherein they have different paths born of the same place and idea.

The

second stanza of the song is a little more confusing, but one could view the

randomly born clouds as the turns of fate or random bits of chance that seem to

govern Chiyoko’s life, as typified in her life seemingly being tied to

earthquakes, and many of the lives of ordinary people. The voice echoed in the

song is said to echo in the moon, meaning that said voice echoes on an eternal

chase to heaven and beyond if the first stanza is any indication of what the

moon representing. In ringing true with the film’s title, said voice is said to

“know a thousand years,” or a millennium, in its echoing in the moon, meaning

that such an eternal chase really is eternal so far as human are concerned. With

that, these first two stanza’s seem to echo a sentiment and idea that one’s

tired old dreams, which have lasted and been pursued for what seems like

eternity, are tied to everyone else’s in them being weighed down by ordinary

life and all the troubles that it holds, but one can overcome that state and

let the turns of fate that have guided said dreams to seize the reigns and make

those dreams bloom anew with the coming dawn.

The

next stanza, or what may be considered the chorus, holds the pair of symbols

that denote the central connections between the song, its title, and a few

scenes in the film itself. The Sanskrit word “Saṃsāra” present in this stanza

has the very important connotation of a rotation-like or cyclic change, or the

theory of rebirth, that is present in the Indian religions. In essence, “Saṃsāra” may be seen as the rotation in “Rotation

(LOTUS-2),” wherein the song’s instrument seem to repeat themselves endlessly

throughout the track. In the “Saṃsāra” blooming, the lyrics may be forming a

connection between the blooming and decay of annual flowers and other plants

and the overall cyclical nature of the film itself, with Chiyoko seemingly

repeating the same few scenes for a majority of her life to no avail in

actually succeeding in catching up with the painter and herself. Chiyoko is in

a time-loop throughout the film, but that loop of time is transported and

changed to meet the present time of her life, with each “failure” leading to a

renewed chase so long as she has her key. With that, the next line’s inclusion

of the “blooming lotus” as a symbol is directly tied to the film itself due to

the facts that Chiyoko both loves and has lotuses in her garden, Genya’s studio

is named “lotus,” and their shared line of dialogue concerning the flower’s

significance. In the above scene near the beginning of the film, Chiyoko and

Genya reveal that the lotus’ meaning in poetry is “simple purity,” with the

camera being fixed on a view of Chiyoko’s blooming lotuses. This image is

repeated throughout the film at other key points, with fog appearing over the

lotuses in a one-off shot near the one-hour point in the film after the

middle-aged and older Chiyoko(s) realize that they cannot remember a single

thing about the painter’s face despite the fact that she resolved to follow him

anywhere and everywhere. In a sense, this is one of Chiyoko’s lowest points,

and one can obviously see the connection between a lotus attempting to bloom and

the wet, thick, moisture-laden, and dewy fog and the very same ideas and

symbols in the song itself, wherein Chiyoko’s dreams are being weighed and

watered down by ordinary life or even reality itself. The lotus, note the

singular use, is next seen at the very end of the film as Genya and Kyoji learn

that Chiyoko is dying. Indeed, the image of the lotus, wherein it is open and

in full bloom while being covered by raindrops and surrounded by fog, is

directly contrasted with the image of Chiyoko on her deathbed in a single cut,

thereby deliberately creating a connection between the dying Chiyoko and the

blooming lotus itself. In this scene, it seems as though the lotus is going to

power through the fog and dewdrops that are weighing it down and shrouding its

beauty by fully blooming and realizing its state without paying any mind to its

surroundings, thereby mimicking Chiyoko’s chase and the life she was able to

lead throughout the most chaotic and turbulent times in human history. In

circling back to the lyrics themselves, the two central symbols may be seen to

directly represent Chiyoko’s chase in the form of ever-rotating Saṃsāra as well

as what she was chasing and her attitude towards life in the form of the simple

purity of the lotus. After these two central symbols, they are said to “echo”

every second for a millennium, perhaps meaning that the blooming cyclical

process of Saṃsāra and the blooming innocence of the lotus will echo and very

much repeat itself for a thousand years, much the in the same way as Chiyoko’s

life story and her chase. This chorus goes on to repeat itself two more times

after the fourth stanza as if to reiterate and rotate back to those symbols and

their significance regarding the film and the song themselves.

In the fourth stanza, the lyrics

point to the fact that the past, present, and future will still exist so long

as the two central symbols of the song stay in bloom and echoing for what seems

like eternity. Those “golden days will exist all at once,” meaning one’s rosy

or youthful past and the promised days of the future will exist, so long as and

“if the forgotten you awakens,” which may be interpreted as the person that

experienced such days as seen in Chiyoko’s case as the young girl she once was.

In effect, these first two lines seen to reflect Chiyoko’s overarching

conclusion that the chase and her key allowed her to hold onto and reconnect

with the girl she was when she met the painter, a young woman that was

captivated by a dream that was shared by her “prince charming” who was to

spirit her away down the path in life that she wished to pursue. Chiyoko’s

memories were unlocked with the key Genya returned to her, thereby breathing

life into the golden days and dreams that she had long forgotten and allowed to

falter. The next line reflects what Chiyoko seemed to have witnessed during her

flight from our world and unto the next, wherein she seems to have seen stars

travelling in parallel. However, it is odd that it is stated that said stars

are “reflected like metaphors,” meaning that said stars may be the very same

ships that the song references earlier, with what seemed to be ships turning

into similar voyages to eternity that are bound together and connected by that

same eternal chase for something. While the stars are literally light years

apart, Chiyoko views them all as travelling in parallel, thereby creating a

metaphor and using it to reflect her feelings at the time, wherein she may be

seen as either powering past such stars, read people chasing something, or

perhaps that she herself is joining their ranks as another eternal and

ever-lasting testament to their endless and continuing pursuits. The latter

seems to mesh well with the next line, “the flowers in the field

which bloom at random are all remembering you,” due to its connotation

that those other stars and chases are all similar to one another and Chiyoko’s

as a result of them being tied to turns of fate and the cosmic randomness of

life and reality itself. The “flowers” that are in existence, perhaps Genya,

Eiko, the old policeman, and Kyoji, will always remember Chiyoko as one of

those distant, parallel travelling stars when, or if, they’ve embarked on that

final journey into eternity because they have been brought together by nothing

other than fate itself, which in this universe, and song, means the universal

randomness of reality. After this realization and final conclusion, the song

goes on to repeat the chorus two more times as if to indicate that this song

and, more importantly, what it describes are eternally repeating and rotating

in a cycle, thereby seemingly repeating, reflecting, and wholly transforming

the film and song into a story about life and eternity.

With

that, this song’s place as the music that sends Chiyoko off into eternity is

fitting as the theme song for “Millennium Actress” specifically because it,

“Rotation (LOTUS-2),” perfectly summarizes the key themes of the film all in

one bombastic and bombing end credits track that effectively and unbeatably

tells the audience that Chiyoko really is continuing her pursuit of the painter

in the next life, with her key in hand and the memories of the girl she once

was firmly at the front of her mind. All

in all, “Rotation (LOTUS-2)” tells the story of how one may come to be Chiyoko

Fujiwara, an aged actress that can bend time, space, dreams, and reality all

with the help of the most important thing there is in the form of her youthful

and undying will, as that is the one thing that has allowed her to weather the

storm of the 20th century and beyond while living the life she

wanted to live. That will, and its timeless echoes, allows the cycle to

continue rotating and for the lotus to fully bloom, leading to the golden days

coming back into existence and the person that one has forgotten to receive a

new lease on life. In the end, the “Rotation (LOTUS-2)” really is the theme

song of “Millennium Actress” because it is as important as the film that came

before it.

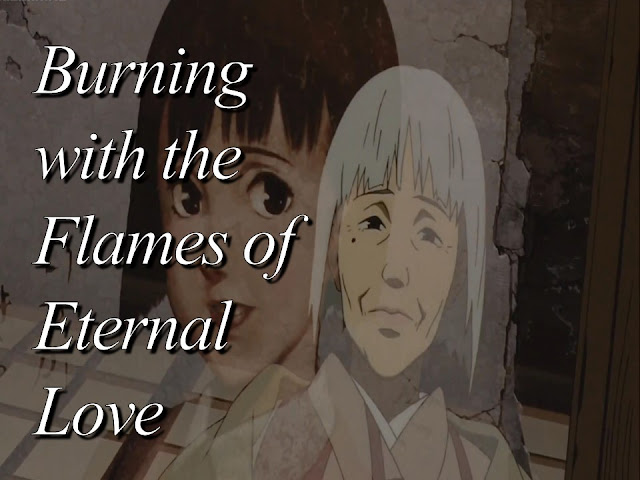

With

the soundscape of Chiyoko’s chase and the film’s theme song out of the way, it

is prudent that one takes a look at the image was, consciously or

unconsciously, created to represent the music and the entire film in a single

image. The image graces the cover of the CD case for the “Millennium Actress

Original Soundtrack,” and it was lovingly crafted by Kon in 2002 while he was

on his way to meet with Hirasawa and his record label to discuss the music of

the film. To quote Kon directly on the process of creating said image:

“Sometimes I have to work

things out, and sometimes images just come to me fully formed. That’s how it

was with this one. I think its true power comes from Hirasawa’s music that this

was a wrapping for. They work together… [Describing the image itself] It’s the

same kimono that she [Chiyoko] wears in the main visual. She has elements of

dreams, like the moon, a crane, a key, and wood grain. It looks like a happy

sleep, curled up like a baby. I think this really captures Chiyoko and

‘Millennium Actress,’ all in one picture.”

To elaborate upon Kon’s reasoning for crafting the image, one could not

understand the film, its music, or even this cover outside of the realm

delineated by the illusion that is the piece of art itself. Simply put, none of

these things exist outside of the illusion in the same sense that they do

inside, thereby channeling the trompe l'oeil motif that pervades the film in

its entirety, with people registering the fact that something is one thing and another. All of these elements are made to work together as a

seamless whole, thereby leading to the music to be just as an essential part of

the film as the story and its themes, along with the image that Kon described. Outside

of the legendary illusion that is the film, these symbols and works are nothing

more than eye and ear candy that do not serve the greater narrative or the

central trompe l'oeil illusion that Kon so painstakingly crafted. With that,

this image can be dissected and analyzed just as acutely and effectively as the

music or film itself.

In

the case of the many symbols that Kon refers to, it is essential that one

understands them all in order for one to comprehend why Kon included them in

his film and the image that graced the cover of the film’s soundtrack. The

kimono is an important part of the image because it denotes and references

Chiyoko’s dual upbringing as both a “modern girl” of the prosperous and

forward-looking 1920s and early ‘30s that reads girl’s magazines and is swept

up in stories of imaginary “prince charming” as well as the “traditional girl”

that is the one that would wear a kimono, settle down in family life, and live

the life that her country needs her to live. These two ideas of how to live

one’s life constantly clash throughout her life, but they are in a harmonious

duality in this image because of what is on the kimono itself. The crane that

is seen on her kimono is a symbol of something that has both lived for a

thousand years, or the millennium in the film’s title, and is a representation

of good fortune and longevity, or the eternal youthful girl that Chiyoko is

pursuing; therefore, the kimono represents both the “modern” and “traditional”

ideals in the crane’s symbolism of eternal youth and the kimono’s symbol of

traditionalism and one’s culture. She is also holding her key, the most

important thing there is to her, in one of her hands with it on display but not

outside of her gaze and grip. The moon, as stated before, refers to endless and

cosmic chases in Japanese culture and storytelling, and it is fitting that

Chiyoko’s story both starts and stops, while most assuredly being shadowed and

lit by, on or near the moon, with it literally forming the part of the

background in this image while also metaphorically forming the backdrop to the

film itself. The wood grain that occupies the rest of the image is reflective,

according to Andrew Osmond in “Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist,” of the natural

mark of aging and growth, with Chiyoko growing older throughout the film while

still actively being on the chase she started in her youth. In the case of her

position of her body, Kon seems to reflect the fact that the young Chiyoko

herself reflects the crane on her kimono, and it actually seems as though this

may have been the idea of herself that Chiyoko was chasing after for a good

portion of her life. However, this line of reasoning can be taken one step

farther in linking the music to said image directly due to said image’s

resemblance of a lotus flower amongst some lily pads, with Chiyoko being the

blooming, bright-orange, young lotus, the moon being the lily pad, and the

expanse of the wood grain serving as a gentle, but aged, pond amongst the

forest. This seems to directly connect the image to ‘Rotation (LOTUS-2)” in

symbolism and theme, with this all being created possibly before Hirasawa began

his work on the music. What a turn of fate it was for this image to appear in

Kon’s mind already fully formed and realized! All in all, this image almost

perfectly reflects the music and the film it accompanies due its similar

symbolism and the fact that such an image’s significance cannot exist outside

the confines of the illusion created by the film; otherwise, it is simply a

collection of weird symbols set as the cover to a weird techno pop album from an

independent musician that has been around since the end of the 1970s.

With

all that being said, I think Kon was right when he said that the image that he

created for the cover of the film’s soundtrack captured the central character

and themes of the film all in one image because it really does reflect the very

same symbols and ideas that are present in both the music and “Millennium

Actress” itself. All three of these pieces are inseparable from one another,

with all three working diligently and effectively to create the overall

illusion that is the experience of the film. As acknowledged by Kon himself,

the illusion of “Millennium Actress” simply would not work without the

soundtrack that reflected and positively transformed the film as it one of the

key pieces that allows one to unlock the puzzle that is the film and reveal the

single, uninterrupted, and enduring continuity that is the fantastical, time

and space bending legend of the eternally running woman: Chiyoko Fujiwara.

~ Sources for Further Reading (&

Listening!) ~